Introduction

A market maker just signed an agreement with a token that you are short… well, it just means more liquidity for traders, right?

Suddenly, a day later, the funding rate plummets to -2.5%, and you’re paying over 2500% APR in funding to maintain your short.

Five minutes later, you’re liquidated. How did this happen?

Welcome to the shadowy side of market-making in the crypto world. In this article, we will explore how market making agreements can have a blur line between supportive liquidity provision and manipulative practices. From token loans and embedded call options to skewed order books and aggressive market manipulation, what should projects and traders look out for?

Key Takeaways

- Market makers provide essential liquidity, ensuring sufficient market volume and facilitating efficient trading. Given the high volatility and fragmented nature of crypto, they are crucial for maintaining stability and liquidity.

- Common market-making fee structures include fixed service fee agreements, token loan agreements, option-based agreements, and performance-based agreements, each with specific terms and caveats. These should be read thoroughly to avoid terms backfiring on the project.

- Alameda Research and DWF Labs illustrate how market-making agreements can be exploitative. Alameda’s agreements often included hidden terms that disproportionately benefited them, while DWF Labs’ aggressive strategies often led to temporary price surges followed by declines. These cases highlight the need for projects to thoroughly understand and scrutinize market-making contracts.

- The line between supportive and predatory market-making practices can blur, making transparency and careful agreement structuring crucial. Projects must align market maker incentives with their long-term goals and perform due diligence to avoid being exploited. Ensuring clear, fair terms in market-making agreements can help protect projects from unfavorable outcomes.

The Role of the Market Maker

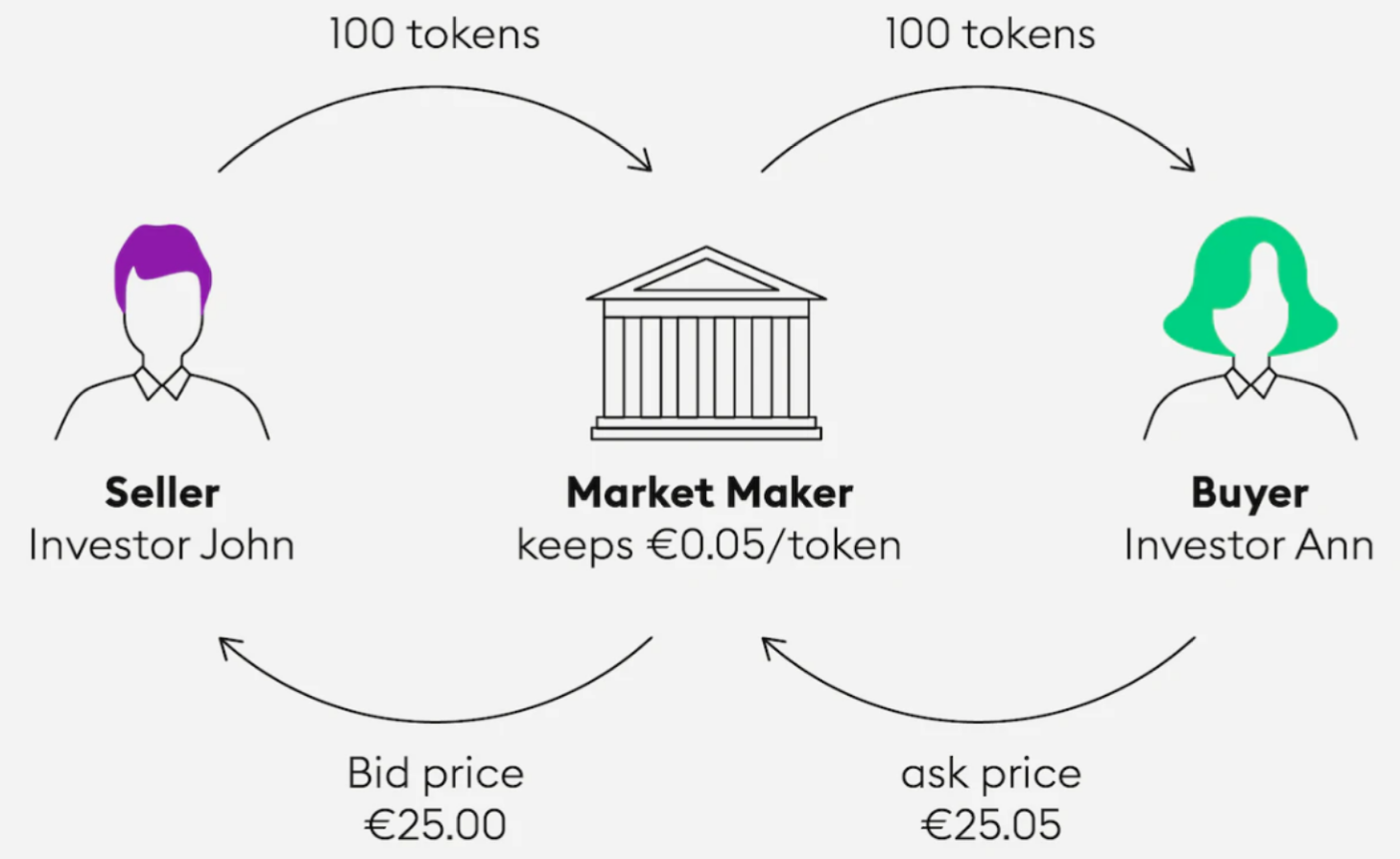

Market makers are financial entities or individuals that provide liquidity to markets by simultaneously quoting buy (bid) and sell (ask) prices for assets, thus facilitating trading. In traditional finance, market makers play a vital role in stock exchanges, ensuring that there is always enough volume for buyers and sellers to execute trades without significant price swings. They do so by maintaining tight bid-ask spreads and deep order books via sophisticated algorithms and high-frequency trading strategies to manage their inventory and balance risk.

Source: Bitpanda

In crypto, the role of market makers becomes even more crucial due to the high volatility and fragmented nature of these markets. Unlike traditional markets, crypto operates 24/7 across multiple decentralized and centralized exchanges, creating unique challenges for maintaining liquidity and stability. Examples of well-known market makers in the space include Wintermute, Cumberland, GSR, and more.

Why are Market Makers Needed?

Eventually, most protocols in crypto will launch their own token. For this token to enter the market and be distributed, it needs to be put into circulation on an exchange, whether it is centralized or decentralized. This liquidity effectively makes the token tradable by allowing market participants to set the bid-ask spread and contribute to a process of price discovery. However, while most projects can control the supply of their own token, they often fall short of the pair asset, which is usually $ETH or a stablecoin like $USDT. Without an appropriate pairing of liquidity between two assets it is not possible for buyers and sellers to meet in the marketplace without significantly altering the asset’s price.

This phenomenon is usually described as a liquidity trap, which is a situation defined by projects needing users to contribute to liquidity before the token can be traded and true price discovery can occur. However, these users will be reluctant to deposit when there is no liquidity. This creates a cold start problem where the absence of liquidity discourages trading activity, which in turn perpetuates the lack of liquidity (i.e. a chicken and egg problem). Without sufficient liquidity, tokens face high volatility, large bid-ask spreads, and inefficient price discovery, all of which can erode investor confidence and hinder both the project’s growth and the token’s supply distribution.

Chart of tokens with thin liquidity (large buys causing massive spikes).

Making Markets Efficient

Market makers are the actual participants that solve this liquidity issue, providing the capital necessary for enabling price discovery. These participants address the liquidity trap in several ways. For example, in an order book they will be responsible for consistently keeping tight spreads (which means that the difference between the highest price a buyer (bid) is willing to pay and the lowest price a seller (ask) is willing to accept is minimized).

Source: River Financial

The way this is achieved in practice is by placing multiple simultaneous bid and ask orders with their own resources (or provided by the project via loans or options) to narrow the spread, therefore making the market. This reduction in spread aims to make trading more efficient, encouraging higher trading volumes. Additionally, market makers help to provide deep order books on exchanges by placing large volumes of buy and sell orders at various price levels. This depth ensures that large trades can be executed without causing significant price movements, thus stabilizing the market and enhancing investor confidence.

Increasing amounts of liquidity play a big role in a token’s price discovery. In a market with low liquidity, price discovery is inefficient because the token price can be easily manipulated by large trades. Market makers, through their continuous trading activity, help in determining the fair market value of the token, reflecting its true supply and demand dynamics. This accurate price discovery is crucial for investors to make informed decisions and for the project to gain credibility in the market.

Because of this, market makers are particularly beneficial during the initial stages of a token listing. New tokens often face near-zero trading volumes, making it challenging to attract early investors. Market makers provide the initial liquidity needed to kickstart trading, reducing early-stage volatility and helping the token establish a stable market presence. This initial boost is vital for building momentum and attracting long-term investors.

Types of Market Making

The term “market makers” are generally used to broadly classify all types of market makers. But you’ll often hear terms like “algorithmic market makers”, “proprietary market makers”, or “market-making-as-a-service (MMaaS)”, which are all slightly different from one another.

Algorithmic market makers use sophisticated algorithms and automated trading strategies to provide liquidity and facilitate trading. They continuously analyze market conditions and adjust their buy and sell orders accordingly. Both “proprietary” and “MMaaS” providers often use complex algorithms to market make.

The core difference is between proprietary market makers and MMaaS. Prop trading market makers typically use their own capital along with loaned tokens to provide liquidity for a pair (usually stables from their balance sheet and tokens that they borrow from projects and return them after a period of time). These firms are profit-seeking, and their revenue comes primarily from trading activities like capturing the difference between the bid-ask spread. MMaaS, however, are more technology-focused and they offer a service where projects can access market-making tools and gain more expertise. The project will then typically pay fixed service fees and provide both the collateral and tokens required for market making. The PnL from trading activities in this case goes to the project itself.

Source: Flowdesk

What Projects Need Market Makers?

Projects typically need market makers at various stages of their lifecycle to ensure liquidity, stability, and efficient trading. Initially, during a token launch, market makers provide essential liquidity to set off trading, reducing early-stage volatility and establishing a stable market presence.

When a project lists its token on major exchanges, market makers ensure continuous liquidity to meet higher trading volumes and the expectations of exchange partners, fostering higher trading activity and improving the token’s market reputation. During periods of high volatility, market makers stabilize prices by absorbing large trades and providing continuous liquidity, thereby maintaining investor confidence and a stable trading environment.

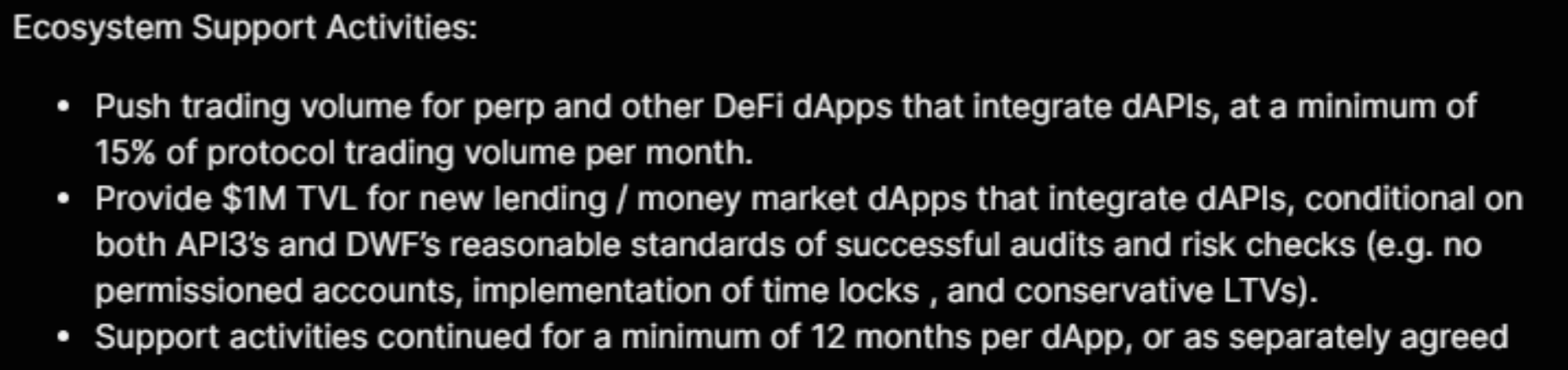

For example, this is how DWF is supporting the API3 ecosystem in their market making agreement (we’ll reference this agreement throughout this article as a case study). Link to the agreement here.

Source: API3

Types of Agreements

There are many forms that market-making Service Level Agreements (SLA) can take. The following are simply broad examples of the more common agreements that market makers have with projects. As an investor, it is key to keep an eye on deadlines and possible updates that might be done in real time.

Fixed Service Fee Agreements

These agreements involve paying the market maker a setup fee and ongoing retainer fees in exchange for providing liquidity. The structure is straightforward, with the market maker committing to maintain tight bid-ask spreads and deep order books. While these agreements ensure continuous liquidity, the fixed costs can be substantial, especially for early-stage projects. Hence, this can be a big barrier to entry and some projects might not be able to afford a CEX listing until later in their lifecycle. Another caveat in these agreements is the potential for high initial and recurring expenses without guaranteed performance outcomes, which makes it less ideal for early-stage projects, as they must take an upfront risk.

This setup is common in MMaaS agreements where the market maker operates in a SaaS-like structure, providing their market making infrastructure and algorithms for the project to configure. Meanwhile, for proprietary market makers, it is less enticing if the early-stage project has a relatively low volume to begin with, which makes it less profitable for them since their earning capacity from bid-ask spreads are limited.

This type of agreement, if used alone, should be done by cash-rich, developed projects when approaching top-tier market makers by offering competitive offers to ensure high-quality liquidity services. Generally, a more developed project would also have higher trading volumes, incentivizing proprietary market makers as they can earn additional profits from the bid-ask spread. Higher trading volumes result in more opportunities for market makers to profit from the difference between the buy and sell prices, providing them with an extra revenue stream beyond the service and retainer fees. This setup creates a win-win situation where the project benefits from enhanced liquidity and market stability, while the market maker enjoys increased trading activity and profitability.

Token Loan Agreements

In token loan agreements, the project provides the market maker with a loan of its native tokens which the market maker uses for trading and liquidity provision. This form of agreement is typically done with proprietary market makers who use the project’s resources to market make. Within the loan agreements are common terms like:

- Loan Amount – This amount is determined based on the liquidity needs of the project and the market maker’s requirements.

- Loan Duration – Specifies the duration for which the tokens will be loaned to the market maker. This period can range from a few months to several years, depending on the terms negotiated.

- Loan Interest – Loans are sometimes provided with an interest rate that the market maker pays to the projects for the borrowed tokens. Typically, this is 0% so the market maker does not take up additional financial burden.

- Repayment Terms – The market maker agrees to repay the loan either in the native tokens or, in some cases, in stablecoins or other assets.

- Usage – The agreement details how the market maker is allowed to use the loaned tokens, primarily for trading and providing liquidity.

For example, in the API3 x DWF agreement, a 1,000,000 token loan is issued to DWF over a 12 month period and DWF has to pay 3% interest every 4 weeks in stables.

Option-Based Agreements

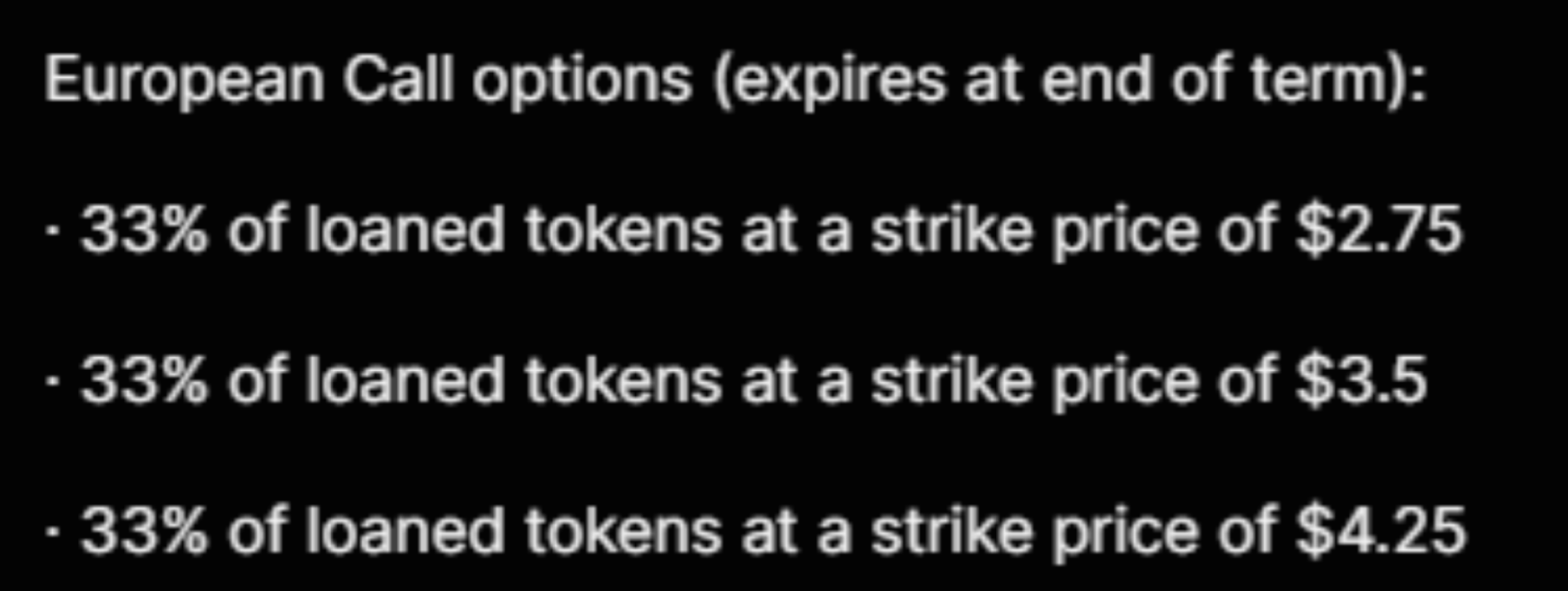

Option-based agreements grant the market maker call options to purchase the project’s tokens at predetermined prices. These are often included hand-in-hand with loan-based agreements as compensation to the market maker. This structure can align the market maker’s interests with the project’s success, as they benefit if the token’s price increases. However, these agreements can be complex and risky. The embedded options can represent significant value, and if not properly priced, projects may unknowingly be giving away substantial upside potential to the market maker, who will be able to capture a large profit off the option delta.

Additionally, the short-term nature of these options can misalign the market maker’s incentives, encouraging them to pump the token price temporarily to exercise their options, followed by a potential dump that harms long-term investors. This also depends on the type of option – American options can be exercised anytime, while European options can only be exercised at the end of the term. We’ll dive deeper into this further below.

In the API3 x DWF agreement, DWF was granted European call options exercisable at the end of the term:

Performance-Based Agreements

These agreements tie the market maker’s compensation to specific performance metrics, such as trading volume, spread maintenance, or price stability. While this structure aligns the market maker’s incentives with the project’s goals, it requires careful crafting to avoid unintended consequences.

A common KPI is for the market maker to maintain an average bid-ask spread within a specified range, such as 0.5% of the token’s price. An unintended consequence here is that even though the spread might be narrow, this liquidity might not be enough if the market maker places only small orders on a very narrow range – this issue is known as lack of depth. For instance, large trades could still experience significant slippage, affecting overall market stability.

Trading Volume is another common potential KPI, and perhaps the most manipulatable one. This KPI sets targets for the market maker to achieve a minimum daily, weekly, or monthly trading volume, measured in either the number of tokens or the equivalent USD value. However, this KPI is vulnerable to wash trading, which is the act of consecutively buying and selling an asset for the sole purpose of drumming up volume and is often illegal in traditional financial markets as it gives a false illusion of supply/demand.

Order Book Depth KPI requires market makers to maintain a minimum volume of buy and sell orders at various price levels within a certain percentage of the current market price. For example, the market maker might be required to ensure there are always at least $100,000 worth of orders within 2% of the current price on both the bid and ask sides. The caveats to this are something called ghost orders, where the market makers place orders that are quickly canceled before they can be executed. This gives the illusion of market depth but does not provide real liquidity when needed. Additionally, beyond the specified range, the books could also be thin.

Price Stability KPIs aim to limit the daily price volatility of the token to within a certain range, such as +/- 2%. This ensures that the token’s price does not experience drastic swings, which can be unsettling for investors. Market makers might artificially control the token’s price to meet stability targets, such as placing large orders to prevent the price from moving beyond the specified range. This can lead to market manipulation and does not reflect genuine market conditions.

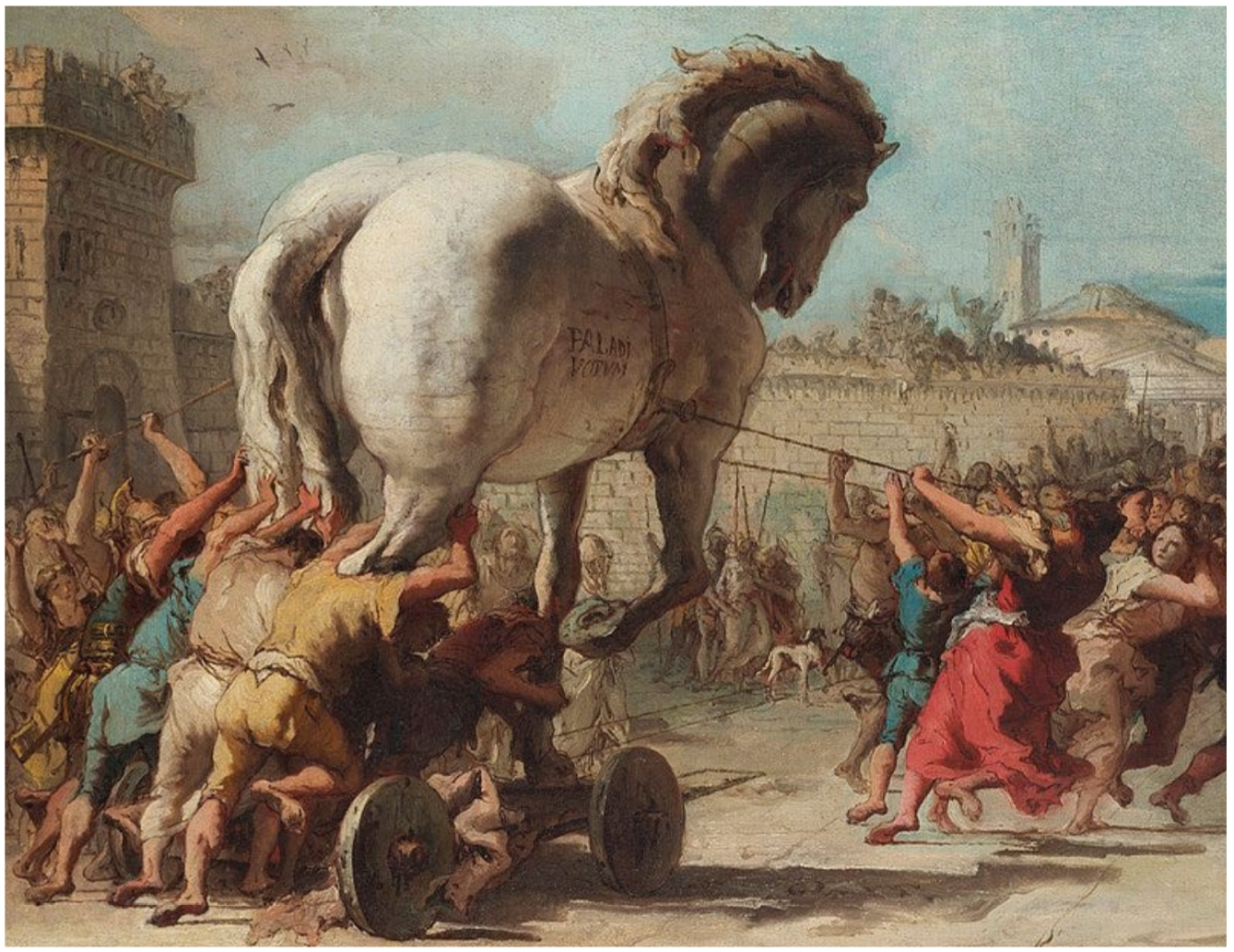

The Trojan Horse

Alameda Research was one of the most renowned market makers during the 2021 bull run, accounting for 2% of daily trading volumes and pulling in an average of $3.5M per day from trading activities. Alameda leveraged its substantial resources and influential position in the market to establish agreements with new projects that often appeared beneficial on the surface but contained hidden terms that disproportionately favored them. These predatory tactics were akin to a Trojan Horse, where the true cost to the projects was concealed within seemingly advantageous market-making agreements.

Alameda commonly structured token loan agreements that included embedded call options. Under these terms, projects would loan their native tokens to Alameda, who would then provide liquidity across multiple exchanges. The agreements often allowed Alameda to purchase a portion of the loaned tokens at a predetermined, typically low, strike price upon the expiration of the loan term.

On the surface, these agreements looked particularly attractive to projects. The project creates tokens out of thin air, gives them to Alameda for liquidity services, does not actually pay with cash, and there’s even a possibility of getting “real” money from the market maker in the form of loan interest or USD loan repayments.

The trojan horse in these contracts is the fact that the token loan can be repaid either in the form of stablecoins or in tokens. If the prices dipped, the market maker simply returned the original quantity of tokens loaned to them. If the prices soar, the market maker returns the loan in the initial USD amount of the loaned tokens, effectively exercising the option.

The problem was the large knowledge asymmetry that existed during the bullrun where projects were rushing to launch a token and trusting market makers with little to no due diligence or skepticism when it came to market making contract clauses. More advanced tactics, such as those often employed by Alameda, involved the introduction of more intricate clauses such as multiple tranches with varying strike prices, or knockout clauses. The added complexity created an illusion of alignment and sophistication, further hindering projects’ ability to clearly understand the contract they were entering into.

The DWF Case

DWF Labs, a subsidiary of Digital Wave Finance, is known for its aggressive market-making strategies and its significant influence in the cryptocurrency market. They have been the center of attention because of their aggressive investments and their tendency to focus on pushing the prices of their partnered project tokens, having only been in the space since late 2022. In H1 of 2023 alone, they have already deployed hundreds of millions into various projects, with multiple 8-figure check sizes.

DWF focuses on 3 primary forms of investments: liquid token investments, locked token investments, and market-making arrangements. In liquid token investments, the firm purchases tokens with stablecoins at a discount (~5-15%), allowing project founders to effectively cash out via OTC deals while maintaining an appearance of receiving significant investment. Locked token investments involve purchasing tokens at a larger discount with a one or two-year lock-up period.

For example, DWF’s $60M investment in Algorand ($ALGO) was an OTC trade that involved DWF Labs purchasing tranches of the $ALGO token over time and was completed in July 2023. Eric Wragge, Algorand’s Global Head of Business Development and Capital Markets, mentions that “At no stage during our negotiations with DWF was there a suggestion of them moving the market or providing artificial volume.”

For market-making services, DWF Labs will often provide its services over a year, and within these contracts would be embedded call options that allow DWF to purchase tokens at a strike price that is typically higher than the current price. DWF often sets this at many multiples of the current price of a token. This means that if the token’s price rises substantially, DWF Labs has the potential to make a higher percentage return.

It was found that across both OTC and market-making deals, prices tend to show a sharp increase averaged over a 6-month increase, with market-making deals often attracting speculative capital which reflexively pushes the prices even higher. Research conducted by LD Capital shows that the price action of DWF-invested coins often follows similar patterns:

Surge in Open Interest and Stable Rates -> Slowing down in the growth of positions -> Decline in rates in the medium term -> Reduction in positions due to longs taking profits.

This is one example with $CYBER.

Source: LD Capital

And another with $YGG.

Source: LD Capital

The price action of these coins often resemble a playbook where the funding rate often dips into heavily negative territories or even maxing out. API3 is an example of a coin that DWF is partnered with. Within their agreement, as highlighted in the case studies above, DWF is offered a loan of 1,000,000 tokens and European call options to buy the tokens in various tranches of strike prices. The agreement was public on January 5 following a 1.5 year-long range, and on January 21, prices suddenly pumped with drastically negative funding rates, trapping and squeezing shorts.

The uptrend continued for a month till mid-February peaking at $4.50, after which it retraced by 50% by mid-April.

DWF also does the same for lower liquidity coins, like memecoins, which result in much larger price impact when it comes to such OTC deals and speculative money inflows. For example, their recent OTC deal with $LADYs (Milady memecoin).

Source: SpotOnChain | “The DWF Labs official wallet 0x53c sent 5M $USDT to the wallet 0xeffb 11 minutes ago

With many of DWF’s wallets being watched on-chain, this often leads to immediate reaction from speculative money, temporarily pumping the prices before slowly bleeding down.

DWF Labs often targets distressed projects that are struggling for liquidity and market traction, like $CFX or $YGG. By injecting funds into these projects, DWF Labs acquires large quantities of tokens at significant discounts. This strategy allows DWF to gain substantial control over the token’s supply, providing them with leverage to influence the market. There has been a long-standing controversy revolving around DWF’s “investing” operations… A lot of these projects often experience a short-lived surge in the token’s price, driven by speculative buying and DWF’s skewing order books to favor buys rather than fundamental improvements in the project.

Conclusion

Market makers are arguably necessary for the crypto space to function, ensuring that there is sufficient liquidity and stability in the markets. While they provide essential services that can benefit projects, the line between supportive liquidity provision and predatory practices can sometimes blur.

It is the duty of market makers to ensure transparency and align their interests with those of the projects they support in order to avoid manipulative practices. But at the same time, projects must understand the deals they are getting themselves into. Otherwise, they risk being exposed to an Alameda-style exploit (unless the project’s market-making goal is predatory too).

As an active market participant, you have the responsibility to do due diligence for trades you enter into, and considering the market makers behind a specific project and their track record should be a part of that process.

References

- API3 Forum

- Mirror Blog: Paperclip Partners

- Mirror Blog: Paperclip Partners

- Mirror Blog: antongolub.eth

- Mirror Blog: Flowdesk

- Mirror Blog: Flowdesk

- Mirror Blog: Flowdesk

- Prestolabs Research

Disclosures

Revelo Intel has never had a commercial relationship with any of the projects mentioned and this report was not paid for or commissioned in any way.

Members of the Revelo Intel team, including those directly involved in the analysis above, may have positions in the tokens discussed.

This content is provided for educational purposes only and does not constitute financial or investment advice. You should do your own research and only invest what you can afford to lose. Revelo Intel is a research platform and not an investment or financial advisor.